As folkorists, we are always questioning what constitutes “tradition,” “transmission,” and “context.”

Mary Hart attended the Keepers of Tradition: Art and Folk Heritage in Massachusetts exhibition twice during its run at the National Heritage Museum. Like many visitors, she filled out a comment card — in her case, the one where we asked people to tell us about a folk art tradition we should know about. Mary described her work in the German paper cutting tradition known as Scherenschnitte.

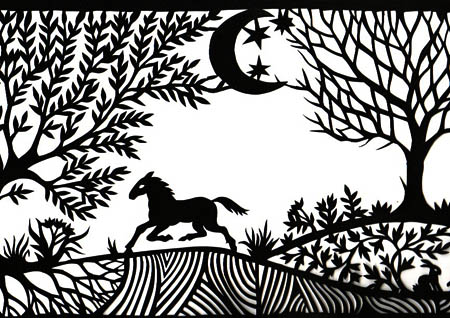

Scherensnitte is a tradition of making decorative documents that flourished within German American farm communities in and around Lancaster, Pennsylvania from the 1750s to the 1890s. People used these cut papers for birth announcements, memorials, love letters, and baptismal certificates. Rather than put them on display, many families stored them between pages of the family Bible.

I was curious about Mary’s paper cutting, but well aware of how she didn’t fit our criteria of traditional artist. Not only did she learn her folk art from a book, she claims no German heritage, and she is what folklorists refer to as a “revivalist,” practicing her art outside of the cultural context in which it was created. After Mary and I exchanged a few emails, I picked up on her frustration of falling in between the worlds of fine craft and folk art, not fully appreciated by either.

Folklorists place great emphasis on the cultural context in which traditions are transmitted. Who one learned from is important. How someone’s work is valued within the community in which the traditional art originated and is practiced is relevant.

So what does a folklorist do with an artist who essentially learned folk art from a book, doesn’t claim any familial or ethnic connection to a tradition, and has a college degree in art? In this case, I drove out to meet with her.

Although Hart has a studio — a small and bright room off the dining room of an open plan contemporary house — she does most of her paper cutting on the dining room table. Before my arrival, Mary had brought out samples of her work, as well as magazines, craft catalogues, and books about paper cutting. She showed me examples of Scherenschnitte, pointing out what attracted her to this German style of paper cutting: the symmetry, the simplicity of the cuttings, and the historical use of recycled papers. Back when paper was not readily available, people reused old letters — not unlike the recycling of cloth in the making of pieced quilts. She also likes the fact that you don’t need specialized equipment to do paper cutting.

Mary creates her own patterns, drawing in pencil. The paper is folded in half. Using an exacto knife, she cuts only the parts that won’t be different once the paper is unfolded. Unique elements are cut only once the paper is unfolded. Her work is traditional in that she uses borders and standard subject matter (farm imagery, trees, flowers, vines). Examples of how she has introduced innovations into the tradition are by adding fruit on the trees, or using a flock of birds.

Like any self respecting artist, Mary would like to be able to sell her work for a fair price and to be appreciated. She also wants to continue being able to teach – she keeps a busy adjunct teaching schedule. Teaching grammar school students is especially gratifying, “I see the visceral pleasure they take in making something with their own hands.”

Mary Hart’s work is beautifully rendered. Is she a folk artist? The folklorist in me must point out that Hart is working in a culturally specific tradition, yet completely outside of the cultural context in which this folk art was created and is practiced. But it is beautiful work, nonetheless.

When work “falls between the cracks” it brings us back to larger questions, such as: How are the traditional arts perpetuated outside of their cultural context? How is tradition reinvented in a transplanted community?

What do you think?

Contact Mary Hart at Jeffrey.Hart@verizon.net

This response comes from Wyoming folklorist Dennis Coelho. I post it with his permission.

Re: The German paper cutter

For me, the key element is the dialectic and dialogue between the

community and the individual artist. The community controls the

aesthetic and all elements of the art form, sometimes accepting

innovation but more often rejecting it in favor of older forms. But

the individual artist is the life-long carrier of those art forms in

much the same way as they carry their own DNA. The artist’s

creativity is bound by community expectation.

Mary Hart is an artist and Arts’ organization have lots of programs

for artists. The fact that the particular art form she is working in

now ( and remember, this is her choice from an infinity of

possibilities) draws from a particular stream of German-speaking

history gives her no special consideration. Other than demonstrating

examples otherwise found in books, she has no connection to Folk Arts

at all. Actually, since she does not interact with any community

tradition bearers, she is not even a revivalist.

The problem arises when these artists want to access the money

available in Folk Arts programs, such as for apprentices, or help in

getting sales or gallery space.

One irony is that graphic artists probably do have their own folklore

made up of stories and legends of gallery owners, judges, materials

sources, famous frauds , etc. But, fo course, that is not what’s

involved here.

Really, Ms. Hart’s situation is no different than if she learned the

German language, from a book, and then applied to the German

government for citizenship based only on her book-knowledge of the

language.

This issue is a real problem in traditional music forms, especially

those forms with any commercial value. How many hundreds of urban

kids have made the pilgrimage to North Carolina to the grave of Tommy

Jarrell, and now with new bib overalls want to be seen as real

mountain fiddle players, complete with a recording contract.

Dennis Coelho

Cheyenne, Wyoming

Her work is gorgeous. Thanks so much for posting it. I’d say that my work falls between the cracks as well. I began as a traditional scherenschnitte artist, but I have moved in a direction away from the tradition.

Just to say that paper-cutting was also found in Jewish communities. I visited a museum in Krakow, Poland, which had examples of Jewish paper-cutting, including a ketubah (marriage contract). The Jewish population of Krakow was sadly decimated by the Holocaust and subsequent emigration to Israel, so the tradition there is being continued by Polish artists.

There is also a separate tradition of paper-cutting in Japan, where it is called kirigami.

Thank you for the beautiful images and your thoughts. I am studying nalbinding, also known as Viking Knitting. It was a lost art. I am surprised to learn that I am not a revivalist (?). When I share my enthusiasm for a rare kind of stitching, that is not called reviving a lost art? Or maybe it is a revival of something ancient, despite the fact that I’m mostly disconnected from the culture of origin… I am grateful for the computers that allowed all these new ideas into my life.

Hi There,

I would like to be in touch with cut paper artist Mary Hart,.

It’s my hope that some one can put me in touch with her.

July 22, 2016