One of the MCC Traditional Arts Apprenticeships being funded this year is to master shipwright and National Heritage Fellow Harold A. Burnham and his son Alden Burnham in wooden boat restoration — a skill that is becoming increasingly endangered. As Harold pointed out in his application, “Since the advent and acceptance of modern materials (mainly fiberglass and steel) for boat and shipbuilding, the wooden shipbuilding industry has all but disappeared, and many of the supporting industries, the requisite skills, and means of passing them on have gone with it.”

The goal of the apprenticeship is to rebuild and restore The Maria, a 23-foot vessel based on the lines of a historic Maine lobster smack. Named for Alden’s grandmother, she was the first vessel Alden’s grandfather built in 1971. The Maria was the perfect size for the young family to sail up and down the New England coast. But in 1972, she was sold out of the family to fund an overseas vacation. When Harold was in high school, he tried to buy her back, offering a more than fair price, but the owner wouldn’t sell. Harold was patient, finally buying the sloop in an estate sale in 2008. By that time, she was in pretty rough shape; large amounts of rot were found in her keel. The MCC apprenticeship was just the incentive Harold and his son Alden needed to finally get to work on rebuilding and restoring Maria.

The family connection was one reason to salvage her, but Harold pointed out others, “There are compelling reasons for repairing or rebuilding an old boat, and as important as the reasons are the lessons that can be learned. Old boats teach you about the materials, the techniques, and the culture of the people that built them.”

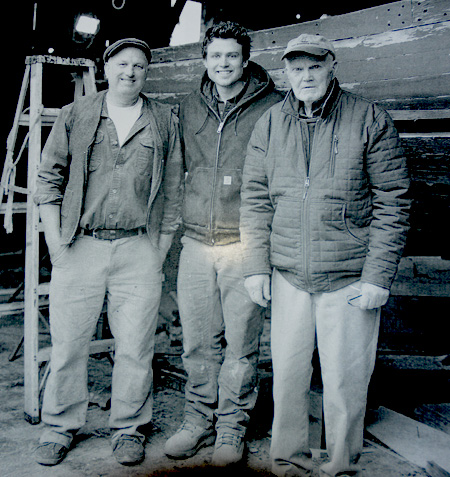

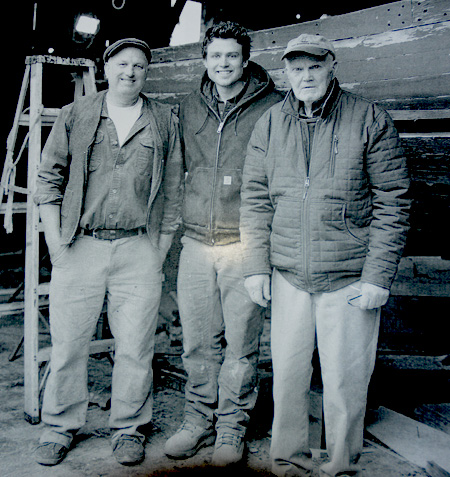

Harold A. Burnham’s life revolves around building or operating boats. He started building and restoring boats in the family shipyard in Essex, where boatbuilding has been not only a family tradition, but part of the culture, dating back to the early seventeenth century. This black and white portrait shows three generations of Burnhams, with Alden in the center.

Although building full-scale historic representations of indigenous fishing vessels for use in cultural tourism has helped rekindle an interest in the region’s maritime traditions, Harold is the first to admit that it has not been a lucrative or easy way of life. “People always used to ask [my father] why he thought he could build boats,” Alden recalls. “His answer to them was simple and yet profound; He knew that he could do it because his father had done it, and he knew people that had done it, and through their efforts, they found a way.”

Alden Burnham, who is now one full year out of college, has grown up around boats. He recalls that when he was 14 years old, an old gray skeleton of a wooden sailboat was dropped in the mud behind their family house on the marsh. He rebuilt the 11-foot turnabout and had a front row seat as the double sawn frame, trunnel-fastened schooners Fame, Isabella, and Ardelle came together outside his house in the shipyard. He appreciates, now more than ever before, what he is father and grandfather can teach him.

We paid a visit to the Burnham shipyard on an unseasonably warm late February morning. Muck and snow melt all around the yard foretold the mud season soon to come. We entered the “barn” where The Maria took up three quarters of the space on the ground floor. We gathered around her to take a look at the progress being made.

Harold, in his characteristic dry humor, remarked, “And you can see, it’s nice and neat in here. No trip and fall hazards.” We watched our step.

“So tell us what we’re seeing right here,” I said.

“Well, you can see that the keel is new. The first thing we did was take the whole keel off and put a new keel in it. All the ribs are getting sisted.”

“Sisted,” I repeated, not familiar with the term. “How do you spell that?”

Alden, who was nearby by a board through the table saw, piped up, “Sistered.” (Sistering is basically a construction term meaning to strengthen or reinforce a structural member by attaching a stronger piece to a weaker one.)

While we were there, Harold and Alden worked independently. Alden was busy preparing new ribs, using the planer and the table saw. The day before, Alden had steamed, bent, and installed seven ribs.

In this photo below, you can see the recently installed ribs which are untrimmed.

While Alden concentrated on planing and sanding ribs, Harold was busy threading and painting a piece of pipe that will connect to the rudder. “That’s really the trickiest part — the mechanical end. Like how to connect the metal to the wood — the engine to the boat, the rudder to the boat.”

It turns out that working on The Maria is the perfect learning situation. In Harold’s words, “This boat is a nice size . . . The nice thing is is that all the installation of an inboard engine, the rigging, the propeller shaft and shaft log and the rudder and all of the geometry of how to put all the metal and wood together, is the same on this as it is on a large boat. This is great learning tool. . . If he falls in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, this boat will be too small for him in fairly short order.”

Five months into the project, Harold and Alden have replaced the keel, sternpost, and worn timber for Maria as well as many frames. They’ve gotten the shaft log ready and the hole prepared for the rudder port. Now that the weather is warming up and the daylight hours longer, they will make real progress. Next up is sistering all of timbers, re-planking her hull, replacing her deck and cabin, installing an engine and systems, building new spars and rigging, and making sails for the vessel. They’ve set a launch date of May 27th.