Master craftsman Bob Fuller was fortunate to have grown up in a boat building family, where he apprenticed under his father and grandfather. The family developed the Edson Yacht Wheel and has been making wheels for Edson International in New Bedford, Massachusetts since 1965.

In 1990, Bob founded his own shop, South Shore Boatworks, which specializes in custom boat building, finishing and restoration work, and handmade wooden ship’s wheels. In fact, Bob Fuller may be the only craftsman in the country today who is still making wooden ship wheels by hand. This highly specialized maritime craft involves pattern making, metal working, marine joinery, and fine woodworking. There are only a limited number of places to learn marine joinery. Although a few boatbuilding schools exist along the New England coast, one of the best ways to learn is one-on-one under the guidance of a skilled master.

Bob Fuller and John O’Rourke were awarded an MCC Traditional Arts Apprenticeship last fall. They typically meet on Sunday mornings from 8:30 to noon. We were there to check in on their progress and observe some of the In late January, Russell Call and I paid a visit to his South Shore Boatworks in Hanson, Massachusetts. You might expect such a place to be situated on the water, but it’s located in an Industrial Park, 30 miles from the coast!

John is a recent graduate of the North Bennett Street School where he earned a degree in preservation carpentry. “I learned mostly historic buildings, nothing about maritime woodwork or marine joinery. In preservation I learned to restore historic structures, historic windows. Try to keep things that were made by hand a long time ago around. So this is very similar. And trying to keep the craft alive.” In contrast, Bob adds, “I don’t work in houses. I chose to work on things where nothing is ever straight. And generally on boats, if something looks straight or looks plumb, it’s wrong.”

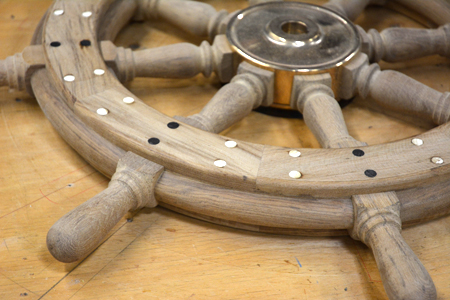

Before showing us what they were currently working on, Bob oriented us by explaining the terminology of a ship’s wheel. “Basically, you’ve got the hub, it’s either bronze or it’s chrome plated, but it’s a piece of bronze. And then you have the spokes. The spokes go from inside the hub out. And then you have the pieces in-between here. I call them segments. Some people call them fellows, which is a word that has more to do with wheel making, like for carts. And then on the top of it, this is a band – it kind of bands things together. And then beyond that, on the spoke, you have the king spoke, which that designates, gives you a reference to where the steering should be neutral.”

These three turnings along the top of the king spoke has always been the family’s signature. “It gives you a sense of feel, especially if you’re operating the boat at night where you can’t have a lot of lights on inside the cabin because it will just blind you, you can’t see out. This way you have a sense as to where the steering is.”

The wheel John was currently working on when we visited is about 2/3rd done. Twenty-eight inches in diameter, it has eight spokes. “There’s a lot that goes into the actual finishing of it, Bob stresses. “Sanding it, hand sanding and then lots of coats of sealer and varnish. . . The wheel I just finished for a customer, the process, the varnishing, was a total of two coats of sealer, and eight coats of hand varnish. And it was a big wheel. It took me roughly two weeks to finish it.” A wheel like this sells for between $2,800 and $3,000. The price can go up from there depending on its complexity, that is, whether is has additional brass band on top or custom engraving on the hub.

In addition to building wheels for Edson, Bob Fuller has customers around the world. Last year he was commissioned to build a wheel for the 50-foot, passenger-carrying lobster boat that services Acadia National Park. High profile wheels include a replacement wheel for Robert Kennedy’s wooden yawl Glide.

It was interesting to hear Bob talk about a recent wheel commission for the new luxury fiberglass motor yacht Cakewalk, built by Derecktor Shipyards. “It was an afterthought. The whole bridge on this boat was set up for using computer settings and all that kind of stuff, but both the captains, an Australian and an American captain, they felt strongly that that boat need a wheel and it would have looked really funny without it. It’s kind of strange today because, with all the computerized stuff — the joy sticks, they call it ‘fly-by-wire’ — a lot of boats don’t have steering wheels anymore. But it’s such a part of our heritage and tradition, that I think it’s going to continue onward.

“We’re preserving the skills to move this forward for a couple of generations. It is just such a part of our maritime tradition, in Massachusetts especially. Shipbuilding, fishing, boat-building, that’s why I feel strongly about this. I learned from my grandfather and father, apprenticing with them. And, if it wasn’t for a situation like what I’m doing with John, I also have someone else that works with me too that’s learning, but not part of the official apprenticeship – where would someone learn this?”

“It’s a great atmosphere when you can teach people the skills that are required to do a craft. It’s been a great opportunity to show this to John in the apprenticeship, to bring a skill forward. . . . this is part of our heritage, as I mentioned before. This needs to be brought into the future. Largely, that’s what the [Massachusetts] Cultural Council is good at, whereas this is such a small niche, it’s hard to, you don’t really fit into someone’s idea of being an industry, but it really is a cottage industry. And that’s what’s kind of going along the wayside. Skills get lost for generations and then all of a sudden, no one knows how to do it anymore.”

Maggie Holtzberg runs the Folk Arts & Heritage Program at the Massachusetts Cultural Council. Photos by Russell Call.

d

d