For several years now, we’ve been trying to track down the Dominican carnival comparsa rumored to be based in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Having seen photos of these fantasic costumed masqueraders, we thought they would be a perfect fit for leading the parade opening the Lowell Folk Festival. Finally, success! We recently visited with Stelvyn Mirabal, founder of the Asociación Carnavalesca de Massachusetts, in his home in Lawrence.

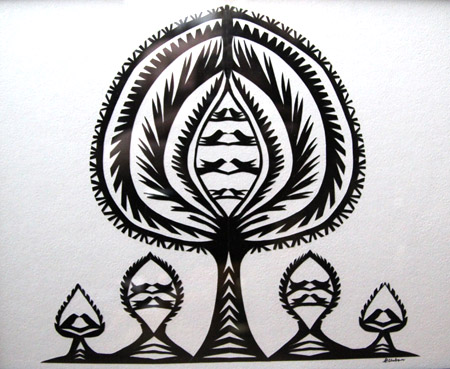

In the Dominican Republic, Carnival is celebrated during the whole month of February, where groups of elaboratively costumed people parading through the streets. Some of the most famous of all the masked participants are the Diablos Cojuelos (limping devils). As the story is told, a demon was once banished to Earth because of his clownish pranks and was injured in his fall, hence the limp. Diablos cojuelos are multi-horned, sharp toothed beings. Many regions of the Dominican Republic have varying versions of this frightening devil.

The Asociación Carnavalesca de Massachusetts brings a bit of Dominican Carnival to the United States. Twelve years ago, Stelyn Mirabal saw the need to preserve Dominican folkloric traditions in Lawrence, where there was (and is) a sizable Dominican population. He formed a comparsa (meaning a group of costumed people who participate in the carnival parade) to take part in Lawrence’s 2nd Dominican Parade. In 2006, he decided to go bigger and brought back 16 masks at the same time. Currently, there are 75 people in his comparsa.

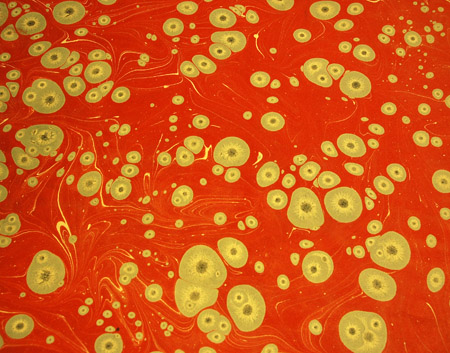

Stelvyn’s home city of Santiago Los Caballeros is known for its style of masks, which are called lechones (meaning pig). They are considered tradicional costumes and are relatively simple; the masks represent pigs or ducks. Suits from the city of La Vega are larger and more elaborate and are referred to as fantasía. The lechones play the role of vejigantes, those who protect the people in the carnival, who, at one time, were members of the royalty. Vejigantes carry and swing inflated cow bladders to keep the crowd away from the parading comparsas. Here in the United States, the cow bladders have been replaced by colorful balloons.

It was Stelvyn’s uncle who taught him and his cousins the carnival traditions of mask making and parading. At age 42, carnival has become a family affair for Stelvyn, “In fact, my mother and my sister, they all dress up. . . My father, a tailor, he used to make the suits.” Below is a photo of Stelvyn’s son Leonardo dressed in a fancy suit and wearing a lechone mask. Leonardo has also become an expert at cracking the whip.

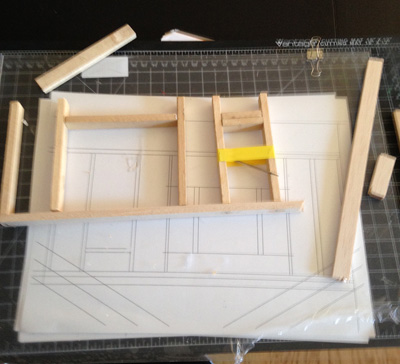

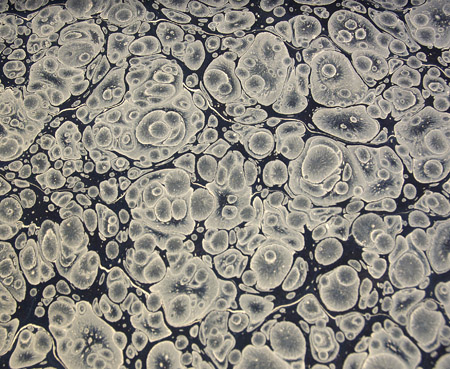

The masks are made from a mold of clay and covered with a paste like papier-mâché. The masks are shined, painted, and decorated. Although Stelvyn knows how to make the molds and papier-mâché masks, he prefers to import them from the Dominican Republic. The more elaborate diablos cojuelos costumes are professionally made using real teeth, horns, and skins, mainly of cows. The Asociación has more diablos cojuelos than lechones because to be a lechone, one has to know how to crack the whip and dance.

One finds Spanish, African and Catholic influences in the tradition. Stelvyn points out a distinguishing feature of the Lechones, “The way we dance is an African dance. So it’s passed generation to generation. We dance different from the guys from La Vega. They jump,” he says, referring to the Diablos Cojuelos. “. . . When we move through the crowd, we try to be like the best horse there is, the Paso Fino.”

Carnival in the Dominican Republic has gotten more elaborate, competitive, and commercial. Stelvyn says there is a move to bring back some of its folkloric roots. “The dances and things have been forgotten a little. So some groups are going back to the traditional.”

Today, the Asociación Carnavalesca de Massachusetts is well known throughout New England for their participation in Dominican and Latino cultural festivals and parades as ambassadors of Dominican culture. You will have a chance to see this spectacular entourage by attending this year’s Lowell Folk Festival. The Asociación Carnavalesca de Massachusetts will be leading the parade on by Friday and Saturday evening of the festival.