FELLOWS:

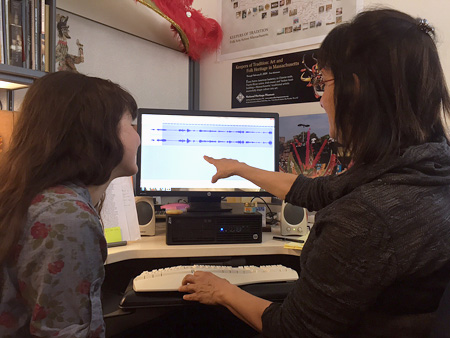

Shannon Heaton, Irish flute playing, singing, & composition

No matter how well any of us play, our Irish cred lies in

how tightly we can play with others. Irish music is social.

Shannon Heaton is highly regarded in Irish traditional music circles for her beautifully expressing playing, composing, and dedication to teaching and promoting the music. She was fortunate to learn firsthand from musicians in Chicago’s rich traditional Irish music scene and later in repeated trips to County Clare, Ireland. For National Heritage Fellow, Seamus Connolly, Shannon’s playing encapsulates the tradition, “In it I hear so many elements of the old styles, such as the playing of Kevin Henry from County Sligo, Ireland, who lived in Chicago and whose music goes back to another time.”

Shannon co-founded the Boston Celtic Music Festival in 2001, a festival that continues to bring Irish musicians together with other Celtic styles. “Live Ireland,” an Irish music radio show broadcasting from Dublin, nominated Shannon “Female Musician of the Year” twice. In addition to performing regularly, Shannon is a sought after teacher, not only of tunes and technique, but also of the tradition’s social and musical customs, e.g., the importance of session etiquette.

Dimitrios Klitsas, architectural and ornamental woodcarving

Both students and seasoned wood carvers come from around the country to study with master woodcarver Dimitrios Klitsas in his studio in Hampden. Like the architects and designers who seek out his impeccably carved ornamental work for fine homes and churches, these students are inspired by Dimitrios’s ability to shape slabs of walnut, mahogany, or oak into breathtaking architectural and figurative works. Guided by his deep knowledge of the fundamentals of classical European design, Dimitrios patiently creates carvings that exemplify both his unique talent and his devotion to the tradition of his craft.

Dimitrios began his training in classical carving at age 13 at the Ioannina Technical School near his home in the foothills of northwestern Greece. After graduation, he served a five-year apprenticeship and then ran his own woodcarving shop in Athens for another five years, before coming to Massachusetts nearly four decades ago. His work here has been recognized nationally with commendations including the Arthur Ross Award for Artisanship from the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. Many of Dimitrios’s students have gone on to professional carving careers, including his son, Spiro.

FINALISTS:

Stephen Earp, redware pottery

Stephen Earp works within the redware tradition, the common name for a variety of domestic, leadglazed

pottery made in New England between the 17th and 19th centuries. Originally, redware was produced to meet the daily needs of food storage, preparation, and serving such as plates, platters, and pitchers. On occasion, redware served commemorative and decorative purposes. Stephen has perfected the functional forms and sgrafitto of Colonial redware, and more recently found his way to his own heritage through making Dutch Delftware.

Most of Earp’s pottery is thrown on a wheel that he designed and built. He uses local materials including clay from a family owned pottery in Sheffield, Massachusetts, which mines clay from a local seam. His glazes include locally dug clay, as well as ashes from the hay of a nearby farmer. In 2007, Stephen was included in Early American Life Magazine Directory of Traditional Crafts. Stephen was named an MCC Finalist in the Traditional Arts category in 2008. He writes an engaging and informative blog, This Day in Potter History.

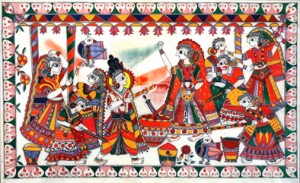

Soumya Rajaram, Bharatanatyam dancer

Soumya Rajaram performs and teaches Bharatanatyam dance, a South Indian classical tradition with strong spiritual connections to Hindu religion and mythology. Although originally a hereditary tradition, the teaching of Bharatanatyam has become institutionalized. Indeed, Soumya came up within a deep lineage of dance teachers trained at the Kalakshetra Foundation in Chennai, India. In addition to her years of dedicated training in the technique and expressive elements of Bharatanatyam, she has extensive training in Carnatic music, which is integral to Bharatanatyam dance.

Known for her exacting standards, Soumya is skilled in nritta (abstract dance) and abhinaya (emotive aspect). She performs regularly at festivals and concerts and is thought of highly by senior dance teachers who first brought Bharatanatyam to southern New England. Soumya is an active contributor to the India arts community in Greater Boston. She continues to enhance her learning under the mentorship of Sheejith Krishna, spending a few months a year at his studio and home in Chennai.

Maria Neves Leite, Cape Verdean singer

Known in the performing world as “Lutchinha,” Maria Neves Leite is a singer of Cape Verdean songs. She was born into a singing family on the island of Sao Vicente, Cape Verde Islands, part of an archipelago off the coast of West Africa. She began singing at age seven, first with her father and later with family friends who would come to the house. Luchinha’s first solo CD Castanhinha bears the title of a mourna that her father wrote for her mother. She went on to become one of the winners at the Todo Munco Canta singing competition, representing her island of Sao Vicente. Engagements in the Soviet Union and in Portugal soon followed.

Lutchinha enjoyed a successful performing career in Europe before she joined her parents in immigrating to the United States. The family settled in Brockton. Lutchinha sang out in the local region, performing for Cape Verdean weddings, Noite Caboverdiana, and other community events. Her repertoire continued to draw from the deep well of traditional Cape Verdean song including the morna, coladeira, batuku,and funana Only recently, with her own children grown, Lutchina has returned to performing outside of the Cape Verdean community, including appearances at major festivals like the 2014 American Folk Festival in Bangor, ME. and the 2015 National Folk Festival in Greensboro, NC where she was backed by an all-star band of Cape Verdean musicians from Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Toni Columbo, invisible reweaving

When is a traditional art at its best when it can’t be seen? Toni Columbo excels at invisible reweaving, French weaving, over weaving, and reknitting; all are traditional ways of repairing holes and damages by hand as imperceptibly as possible in woven and knitted fabrics. Threads or a frayed piece of fabric are harvested from an inconspicuous spot on a jacket, pants, coat, or sweater, and rewoven thread by thread, into the damaged area, rendering it virtually invisible.

Toni learned needle arts from her mother, who in turn, learned from her mother. Toni was born and raised in Boston’s North End, and she maintains a vital connection to this Italian American community. She is highly regarded by customers and by high end retail stores for her excellent skill in mending cherished items of clothing. Using the skills passed down through her family, Toni repairs and restores suits, sweaters, coats, couches, tapestries, and uniforms (including Babe Ruth’s 1926 New York Yankees baseball jersey). In addition to working on heirlooms, Toni keeps up with the new weaves and fibers used in today’s textiles. To work on these micro fabrics, some containing between 100-125 threads per inch, Toni uses a high powered surgeon’s loupe.