Here are a few more craft artists you can look forward to meeting in the folklife area of the 2017 Lowell Folk Festival. Native craftspeople from Massachusetts and Rhode Island will be in Lucy Larcom Park, demonstrating and talking about their work with quahogs, deer antler bone, and copper.

And in one tent, it will be a family affair. Patricia James-Perry and her children James and Elizabeth are highly skilled artists whose work draws inspiration from the skills and craftsmanship of their Wampanoag ancestors.

Patricia James-Perry’s family roots are deeply planted in Wampanoag ancestral lands on Aquinnah, Martha’s Vineyard. One could say she was born into the tradition of scrimshanding, the once common art of hand-crafting decorative and functional items from salvaged whale ivory. She fondly recalls the abundance of scrimshaw in her 1940s-childhood home in New Bedford – her grandmother’s ivory sewing needles, pendants inscribed with tiny whaling scenes, niddy-noddies for yarn, rolling pins, and pie crimpers.

The Wampanoag people of Massachusetts/Eastern Rhode Island were inshore whale hunters and later heavily involved in New England’s global whaling industry. Gay Head whalers were prized for their hunting prowess and navigational skills. Patricia’s grandfather, Henry Gray James, was a career whale man, as was her uncle, Joseph Belain. Family stories tell of Belain twice leading captain and crew to safety, after their ship became ice-bound in the Arctic.

Patricia inherited her whaling ancestors’ tools and her families’ supply of whale teeth. In the 1970s, she carved scrimshaw at LaFrance’s Jewelers in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

With small children, making scrimshaw became difficult for Patricia, along with changing laws governing marine mammal items. Patricia is making scrimshaw again, but now using polished deer antler. Elizabeth and Jonathan James-Perry plan to apprentice with their mother, keeping scrimshanding in the family and maintaining the Native identity it rightly deserves.

Wampum artist Elizabeth James-Perry is a member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head Aquinnah. Her work is strongly influenced by finely crafted ancient wampum adornment and lore, as well as her late Wampanoag mentors and cousins Nanepashemut and Helen Attaquin.

Elizabeth harvests quahog and conch shells from local waters, sorting them by size and color. Using the rich layered purples of the quahog shell and softer conch shell, Elizabeth sculpts patterned whale and fish effigies and thick wampum beads.

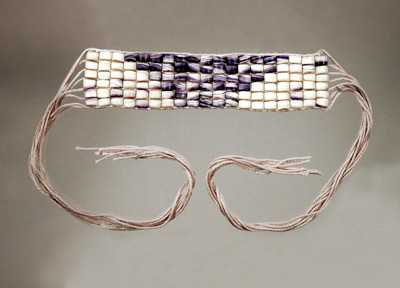

Her earrings often contrast the purple and white of quahog shells with the white of deer antler or bone. The combination gives the earrings color and textural variety, while subtly expressing the link between land and ocean. Using shell appliqué, she makes star medallions and finely-woven wide purple gauntlet cuff bracelets, both emblems of traditional Native leadership.

Elizabeth’s art is a form of Native storytelling and genealogy relating to coastal North Atlantic life. She grew up watching her mother Patricia execute tiny whaling scenes on bone scrimshaw, and shared her Wampanoag families’ whaling history in Living with Whales, a book by Nancy Shoemaker. When the historic whaling vessel Charles W. Morgan was newly refurbished, Elizabeth sailed on-board its 38th voyage as a descendant of the Gay Head and Christiantown tribal crewmembers. In 2014, she was awarded a Mass Cultural Council Artist Fellowship in the traditional arts.

Jonathan James-Perry grew up in a creative household surrounded by music, sculpting, beadwork, and scrimshaw, all coming out of rich Wampanoag traditions. He practices an impressive variety of indigenous art forms including making effigy pipes, copper jewelry, engraved slate pendants, burl bowls and platters, wooden hair combs incised with Native motifs, boat paddles, boats, and flint knapped stone tools. He works with locally sourced woods, stone, and metals.

His preferred metal to work in is copper as it holds a special meaning and significance for Eastern Native people. “Copper’s reflective surface is evocative of the warmth of the sun and is considered medicinal as well as being ideal for adornment.” Jonathan cold hammers and draws out the metal, forming long copper thunder bird breastplates, lunar gorget neck plates, and gauntlet cuffs. He then hand-presses designs into the metal’s smooth finish, embossing them with either abstract edge work or clan animal shapes. These embellishments are inspired by those found in ancient Wampanoag material culture — basketry, tattooing, stone carving, and pottery stamps. Concave discs represent the moon, a repeating double curve may represent growth or a whale’s spout out on the ocean. As a 2017 Community Spirit Award recipient from the First Peoples Fund, Jonathan is committed to passing on his knowledge to the next generation.

In an adjacent festival tent, you will find Narragansett wampum artist Allen Hazard, who has been making wampum for the last 30 years.

Among Eastern Woodland Tribes, wampum has traditionally been used as adornment in the fashioning of beads for necklaces, earrings, and belts and as a medium of trade. Allen shares that the word “wampum” comes from the Narragansett word for ‘white shell.’ The quahog is a hard shell clam once found in abundance along coastal New England waters. The meat of the quahog has long been valued as a source of highly nutritious food. The white shell and deep purple inside of the shell continues to be highly prized as a material for fashioning beads.”

Allen acquired his skills from his mother Sarah (Fry) Hazard and other Narragansett elders as a child. Creating a single tubular bead from the hard shell of the quahog is a time-consuming task. Using replicas of old school wampum tools, Allen let’s people see how wampum beads were created before the availability of power tools. He has introduced modern tools into the process, including a wet saw to cut the clamshell, and a Dremel to smooth, bore, and polish the final product.

Allen’s wampum beads, necklaces, and belts are made in an old style so they can be worn with traditional Eastern Woodland regalia. He and his wife Patricia run the Purple Shell store in Charlestown, Rhode Island.