Ever since the industrialization and mechanization of labor, there has been less need for the singing of work chants. But back in the day, a special kind of singing helped work get done, whether it was sea chanties used to raise sails, Scottish waulking songs used to work wool, or agricultural work chants to hoe cotton or cut timber. In the deep south, such work chants were common among African Americans who labored under extremely harsh conditions. A good song was like a labor saving device. Singing work chants helped coordinate movements and build on collective strength. They also ensured safety for railroad gangs working in small crews with heavyand sharp tools. And, perhaps more importantly, these chants uplifted the men’s spirits.

One man, known as the caller, would stand aside from the crew and sing verbal instructions. His commands were answered by the men’s lining bars wrapping in rhythm against the railroad track– in a call and response manner. I came to know this tradition (or what remained of it in the minds of retired railroad workers) first hand while doing field research for the Alabama State Council on the Arts in the late 1980s. We interviewed half a dozen former track laborers and eventually produced the film Gandy Dancers, which tells the story of African American railroad workers who made their living building and maintaining the railroad lines that crisscross the American South.

I recently uncovered a connection between the southern African American tradition of call-and-response works songs and military cadence calls used in drill training, popularly known as “Jody calls.” Anyone who has gone through basic training is familiar with these military cadence calls. A drill instructor, whose job it is to keep recruits in step while training, calls out marching orders. Cadence calls motivate, while ensuring unit cohesion and promoting military discipline. Safety is a factor as well, especially while marching or running in close formation. Similar to the railroad workers’ calls, military cadence calls are also a way to take one’s mind off strenuous tasks, vent dissatisfaction, mock one’s superiors, or build morale by boasting, poking fun, or talking dirty. As verbal art forms, both have a rich tradition.

Popular legend holds that that Private Willie Lee Duckworth Sr. (1924-2004) made up “Sound Off”, a.k.a., the “Duckworth Chant,” which is used to this day in the U.S.Army and other branches of the military. The year was 1944 and Duckworth was stationed at Fort Slocum, New York as one of eight “Colored Infantrymen.”

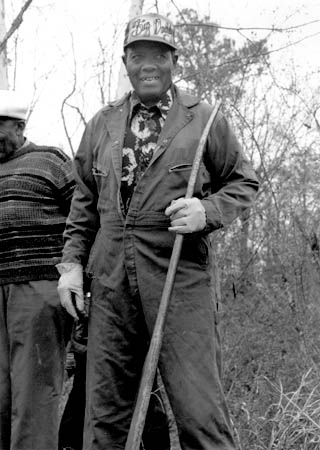

Duckworth, who was born in 1924 in Washington County, Georgia, would have been familiar with the use of work chants sung for all kinds of agricultural work. He was also the same generation of the gandy dancers who used chants to line track. At the time he was drafted to serve in WW II, Duckworth was working in a sawmill. He was sent to a provisional training center in Fort Slocum, N.Y., in March 1944. As the story goes, Duckwork, on orders from a non-commissioned officer, improvised his own drill for the soldiers in his unit. Soon after, all the ranks were buzzing and keeping rhythm. Col. Bernard Lentz, who was the base commander at the Fort, approached Duckworth and asked where he developed his unique chant. “I told him it came from calling hogs back home,” Duckworth said. “I was scared, and that was the only thing I could think of to say.”

Colonel Bernard Lentz was so convinced of the cadence calls’ effectiveness that he made them standard at Fort Slocum and went on to write a drill instruction manual. The “Duckworth Chant” was popularized in 1945 when the US government included it with other popular music of the day on a V-disc (12 inch vinyl 78 recording) for distribution to US military personnel overseas. The chant later gained fame as “Sound Off” and remains one of the most popular marching cadences in Army history.

Join us at a free public program on February 27 at Lowell National Historical Park Visitor Center. In addition to screening the documentary Gandy Dancers, we will play the original recording of the “Duckworth Chant,” screen contemporary examples of cadence calls, and present a live demonstration by a military drill sergeant.