What does it mean when ancient holdidays, grounded in ethnic identity and religious belief and celebrated by cultural insiders for centuries, are brought to mainstream, high profile venues to be shared, celebrated, and interpreted? Who benefits? What is gained and what is lost when a festival moves from private space (a temple, a home) to a public space (a state house, city hall, or museum)? How is cultural meaning negotiated?

For the last five years, Amit Dixit, the leading light behind the South Asian Arts and Cultural Council, has organized an annual Diwali lighting ceremony at the Massachusetts State House.

The invitation to attend describes Diwali, popularly known as The Festival of Lights, as “. . . the most sacred of Indian holidays celebrated by Hindu communities throughout the world, including those in the Indian diaspora together with worshipers of Hinduism in Nepal, Singapore, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka. The holiday is the embodiment of the supremacy of divine light over spiritual darkness, of knowledge over ignorance, good over evil, and hope over despair. Diwali is associated with great optimism, generosity and, most importantly, new hopes for the future.”

Those attending the State House event on October 29, 2016 were a mixture of cultural insiders, government employees, and members of the general public.

An official from The United States Postal Service was present to help unveil the Diwali forever stamp.

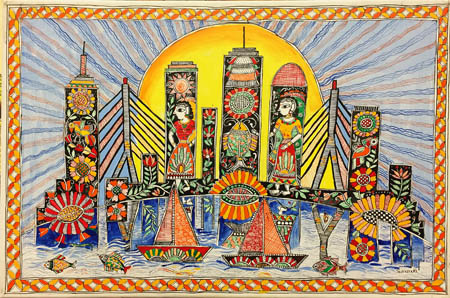

Diwali is celebrated for seven days every autumn. This year Diwali officially began on Sunday, October 30 and ran through Saturday November 5. Mid-way through, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston held its own celebration of the Festival of Lights. On offer was a splendid variety of South Asian expressive traditions including music, dance, Madhubani and Mithila art making, and a moderated discussion about Diwali in Boston and around the world.

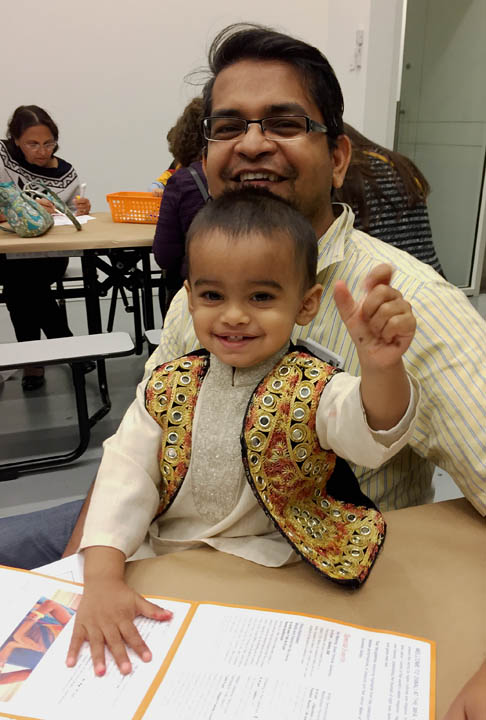

Having the MFA celebrate Diwali helps legitimize the expressive traditions of lesser known cultural communities. As Saraswathi Jones (second from left), who grew up in one of the only Bengali families in Grand Rapids, Michigan put it, “It’s meaningful. It’s validating.”

In writing about Washington DC’s Latino Festival (1991), Olivia Cadaval says, “The festival transforms physical space into a means to cultural identity. As a temporary center of power, the festival brings together large numbers of Latinos, unifies space, and generates action, during which symbols and traditions are manipulated, cultural forms are given expression, relationships are negotiated, and new social identities are forged.”

Although it’s a vastly different culture and a different time, I believe Cavadal’s observations still hold true. In addition to introducing cultural outsiders to Diwali, the public acknowledgement of an ancient holiday rooted in Sanskrit and prayer trumps linguistic, regional, and national differences, creating solidarity among South Asians who make Massachusetts home.

Things work best when ethnic self-representation and institutionally curated presentations are done collaboratively. It’s a win win.The MFA’s event planners are to be commended for working with cultural insiders to interpret and present expressive traditions that might otherwise be little understood by cultural outsiders.