In the Fall of 2016, we wrote about the Hindu festival of Diwali going mainstream. We wondered what it means when ancient holidays, grounded in ethnic identity and religious belief and celebrated by cultural insiders for centuries, are brought to mainstream, high profile venues to be shared, celebrated, and interpreted?

Two years later, we hear from Sunanda Sahay, a traditional artist who practices the North Indian art of Madhubani (also known as Mithila). She describes her 10th year of sharing her art at the Museum of Fine arts. Here is her guest blog post.

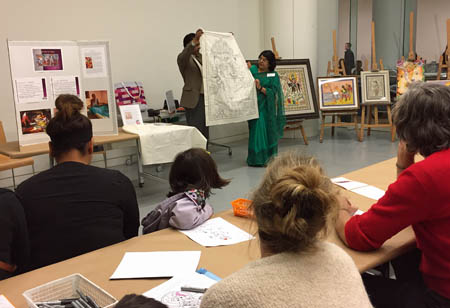

For several years now, the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) has been celebrating the joyous Indian festival of Diwali in early November. I am fortunate to have taken an active role by conducting folk art workshops/exhibits. This year, the event took place on Wednesday November 7th which coincided with the day of Diwali, making me wonder if that would drop attendance.

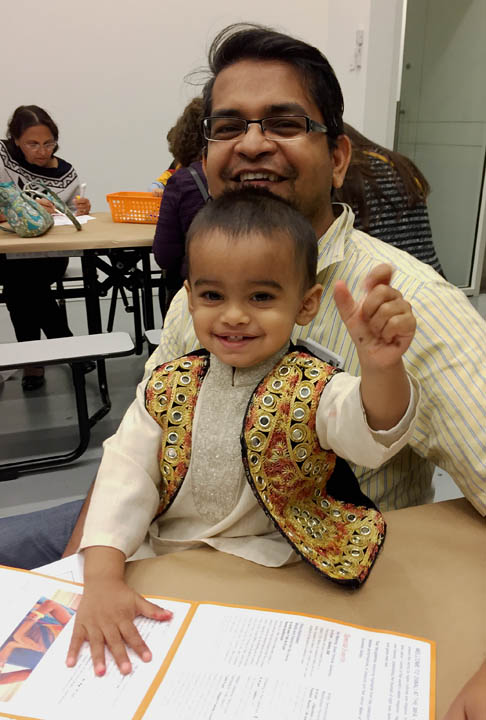

Lo and behold! The visitors swelled as the evening rolled in. Since I have been organizing the workshops at the museum for many years, I thought I was prepared to handle the crowds. But the unprecedented crowd and long lines at the museum caught me totally off guard! While some of the visitors managed to find seats to sit down and draw, the others looked around at the paintings or rotated through the room. Thanks to the immense support and patience of the museums staffs and volunteers, many were able to sit down and create their own artwork they could carry home.

For the first time, more than a dozen of my students ranging between 7 years to 47 years of age exhibited their art and assisted with the workshop. They reveled in the glory of being a part of one of the best museums in the world! They excitedly helped the attendees, answered various questions, and proudly shared the stories behind their creations. It seemed that the room had turned into a village celebrating its own version of Diwali – strangers sat together and talked, encouraged each other, suggested and commented on the art pieces, and just enjoyed the atmosphere of shared creativity. Some of them sat down hesitatingly, but then quickly surprised themselves with the brightly hued wonderful forms they created with the simple motifs. This is what I love about my art!

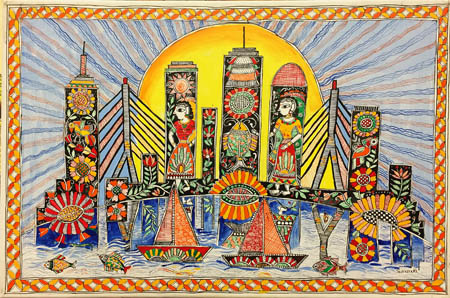

Folk arts have this special ability to form communities. In my home town where Madhubani/Mithila art has been practiced for centuries, women get together and paint murals on their homes to depict scenes from traditional epics, festivals, and village activities. Art is essential to the living cultures. The process of creating visual stories forms social bonds not only between the women creating the art, but also between other adults and children who inevitably become part of the stories.

When I held the first MFA workshop in 2009, I could have scarcely imagined that the event would recreate social ambiance similar to the native villages. Initially, it was a personal and a creative challenge, and I endeavored to create something new and unusual each year. In addition to the Madhubani art, I also introduced other folk art forms such as Warli to the visitors. I made sure they understood the art’s historical background as well as its continued survival through cataclysmic changes and growth. And I encouraged the visitors to not only paint the traditional themes but also push the boundaries, and use their imagination to tell modern stories through an ancient medium. My students certainly heed my advice; one of my apprentices created a Disney story in Madhubani and everyone loved it.

I regularly run into people who know about this annual workshop and look forward to the event. More and more Bostonians are becoming familiar and appreciative of the folk arts of India and I am hopeful that at least this folk art will not die under the constant onslaught of digital intervention and lack of support.

Guest blog by Sunanda Sahay of Acton, Massachusetts