As folkorists, we are always questioning what constitutes “tradition,” “transmission,” and “context.”

Mary Hart attended the Keepers of Tradition: Art and Folk Heritage in Massachusetts exhibition twice during its run at the National Heritage Museum. Like many visitors, she filled out a comment card — in her case, the one where we asked people to tell us about a folk art tradition we should know about. Mary described her work in the German paper cutting tradition known as Scherenschnitte.

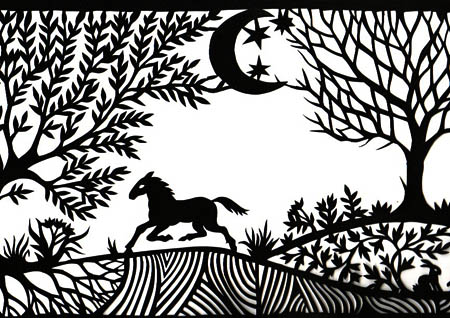

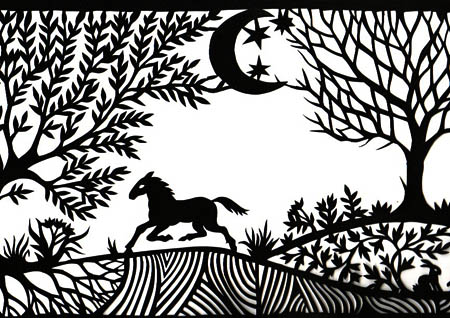

Scherensnitte is a tradition of making decorative documents that flourished within German American farm communities in and around Lancaster, Pennsylvania from the 1750s to the 1890s. People used these cut papers for birth announcements, memorials, love letters, and baptismal certificates. Rather than put them on display, many families stored them between pages of the family Bible.

I was curious about Mary’s paper cutting, but well aware of how she didn’t fit our criteria of traditional artist. Not only did she learn her folk art from a book, she claims no German heritage, and she is what folklorists refer to as a “revivalist,” practicing her art outside of the cultural context in which it was created. After Mary and I exchanged a few emails, I picked up on her frustration of falling in between the worlds of fine craft and folk art, not fully appreciated by either.

Folklorists place great emphasis on the cultural context in which traditions are transmitted. Who one learned from is important. How someone’s work is valued within the community in which the traditional art originated and is practiced is relevant.

So what does a folklorist do with an artist who essentially learned folk art from a book, doesn’t claim any familial or ethnic connection to a tradition, and has a college degree in art? In this case, I drove out to meet with her.

Although Hart has a studio — a small and bright room off the dining room of an open plan contemporary house — she does most of her paper cutting on the dining room table. Before my arrival, Mary had brought out samples of her work, as well as magazines, craft catalogues, and books about paper cutting. She showed me examples of Scherenschnitte, pointing out what attracted her to this German style of paper cutting: the symmetry, the simplicity of the cuttings, and the historical use of recycled papers. Back when paper was not readily available, people reused old letters — not unlike the recycling of cloth in the making of pieced quilts. She also likes the fact that you don’t need specialized equipment to do paper cutting.

Mary creates her own patterns, drawing in pencil. The paper is folded in half. Using an exacto knife, she cuts only the parts that won’t be different once the paper is unfolded. Unique elements are cut only once the paper is unfolded. Her work is traditional in that she uses borders and standard subject matter (farm imagery, trees, flowers, vines). Examples of how she has introduced innovations into the tradition are by adding fruit on the trees, or using a flock of birds.

Like any self respecting artist, Mary would like to be able to sell her work for a fair price and to be appreciated. She also wants to continue being able to teach – she keeps a busy adjunct teaching schedule. Teaching grammar school students is especially gratifying, “I see the visceral pleasure they take in making something with their own hands.”

Mary Hart’s work is beautifully rendered. Is she a folk artist? The folklorist in me must point out that Hart is working in a culturally specific tradition, yet completely outside of the cultural context in which this folk art was created and is practiced. But it is beautiful work, nonetheless.

When work “falls between the cracks” it brings us back to larger questions, such as: How are the traditional arts perpetuated outside of their cultural context? How is tradition reinvented in a transplanted community?

What do you think?

Contact Mary Hart at Jeffrey.Hart@verizon.net