I grew up, like most people in this part of the world, eating European style chocolate. So having this Mexican traditional chocolate was revelatory.

Alex Whitmore, Co-founder of Taza Chocolate

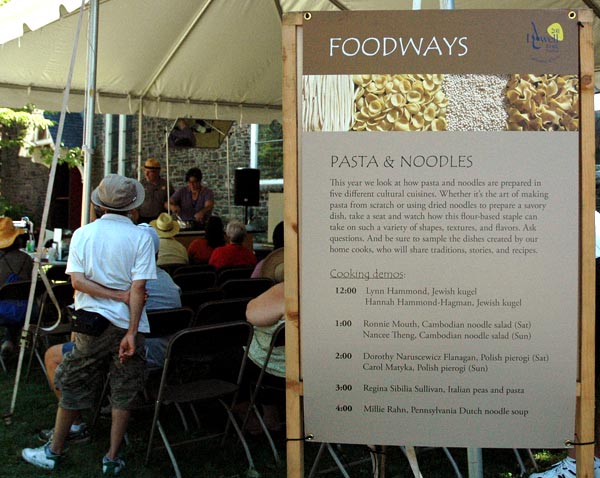

If you attended last summer’s Lowell Folk Festival and wandered into the foodways tent in Lucy Larcom Park, you would have seen (and tasted) that we were into beans. Cooks representing five different cultural cuisines shared their favorite bean dishes with the crowd (750 servings in all).

In an upcoming public program at Lowell National Historical Park, we will be exploring a different kind of bean. Just two days before Valentine’s day, we will present a program on the Mexican tradition of manufacturing, baking, and cooking with chocolate made from stoneground cacao beans.

As the date approaches, more info will be posted, but in the meantime, I thought I’d share some details from my recent visit to Taza Chocolate, a Mexican-style chocolate factory in Somerville, Massachusetts.

My guide was Alex Whitmore, co-founder of Taza Chocolate. Taza is one of several businesses located in an industrial building near the Cambridge/Somerville border. Walking into the main entrance, I was immediately overwhelmed by the pleasant aroma of chocolate. If only one could record smells . . .

As companies go, Taza Chocolate is fairly new. Established in 2006, Taza is dedicated to manufacturing minimally processed chocolate made from fair trade organic cacao beans. Rotary stone mills from Oaxaca are used to grind the roasted beans.

Before touring through the factory, Alex and I sat down for an interview. Turns out, Taza is one of only 18 companies in the United States that are a “bean to bar” chocolate manufacturer, meaning rather than buying processed chocolate, they actually make chocolate from cacao beans bought directly from growers in Central America.

The majority of businesses making and selling chocolate are called “chocolatiers.” They may make delicious chocolate candy but they buy they don’t start by roasting and grinding their own cacao beans. The smooth, melt-in-your mouth chocolate we associate with Swiss, Belgium, and Italian confections is a relative newcomer on the scene. As Alex reminded me, the indigenous peoples of Central and South America consumed chocolate primarily as a drink for thousands of years before the delectable substance was introduced to Europeans. “The [cacao tree] is indigenous to Central and South America. And because of that, it became culturally important as a food stuff in the early civilizations of the Americas. The Europeans didn’t actually get their hands on the cacao bean until after the Columbian exchange when the Spanish brought it back over to Europe. They didn’t really start making chocolate as we know it today, in a solid form until the late 1700s, early 1800s. And It wasn’t really developed until the mid to later 1800s as a fine candy.”

The chocolate made at Taza differs significantly from chocolate manufactured around the United States. “We make chocolate in a very specific tradition . . . The entire process is very much inspired by Southern Mexican chocolate making.”

Cacao beans come from the theobroma tree, which grows best in a hot and humid climate. The fruit of the theobroma tree is a cacoa pod, which contains seeds called beans. Alex points out that “Because Taza chocolate is made with such minimal processing, our product tastes like our ingredients.” What this means is that it is really important for the company to personally source their beans, buying directly from farmers with which they have developed a personal relationship.

Once the beans are harvested, they are fermented and dried before being shipped to Taza. Fermentation creates more complex flavors. Alex made the comparison between the taste of flour and water, like matzoh (unleavened bread) to the more complex taste of bread made with yeast.

I asked Alex about his time in Oaxaca, Mexico, where he studied under several molineros (Spanish for stone ground millers.) In this part of Mexico, being a molinero is a family tradition which is passed down from father to son and kept rather secretive. Although Alex learned a good bit about dressing the grinding stones, he was never allowed to see stones with freshly cut patterns.

As is done in Mexico, Taza uses granite milling stones to grind their cacao beans. They hand chisel each millstone with a pattern specifically designed for grinding chocolate.

Stone ground chocolate, like stone ground grain, leaves granular bits behind, which gives Taza chocolate its rustic texture. After our interview, Alex led me through the factory to see various stages of production – winnowing, grinding, roasting, tempering, molding, and packaging. Taza also runs a retail store, and offers factory tours to the public three times a week.

If you’d like to meet Alex and learn more about their unique products and philosophy, plan on attending our program on February 12, 2011 at Lowell National Historical Park — Visitor Center. Details to follow.