It’s that time of year when we are busy selecting craft demonstrators for the Lowell Folk Festival. Our theme is textile traditions and for the past several months I’ve been traveling to meet with people who are passionate about hand crafting textiles out of wool, cotton, and linen.

In Colonial New England, prior to the availability of manufactured goods, women were primarily responsible for the production of household textiles. Cloth was woven out of homespun cotton, wool, and flax; quilts were pieced together from worn out clothing and feed sacks. Women sewed the family’s clothing, hooked rugs, and knitted sweaters and mittens.

Of course, the late 19th century Industrial Revolution changed all this. As pictured above in Sally Palmer Field’s Mile of Mills wall hanging, Lowell is the birthplace of the American textile industry. Once fabrics were manufactured locally, they became more affordable. Today, the majority of textiles we use are commercially manufactured halfway round the world. Buying hand-crafted textiles has become something of a luxury. What began as basic survival skills — weaving, knitting, quilting, and rug making — has evolved largely into expressions of creative artistry. The craft artisan’s purpose/market has changed too – from domestic necessity to supplying craft fairs and galleries, and engaging tourists at living history museums.

This is especially true when it comes to the time-consuming, exacting production of bobbin lace. As Linda Lane, a master lace maker points out, “It can’t really be done on a commercial basis because one square inch of lace takes approximately an hour. Due to its complexity and the fineness of the lace, that can be days. So immediately, you price yourself out of a demand market.”

An accomplished weaver and spinner, Linda Lane learned to make lace by watching another lace maker for a number of years. Then, with the aid of a few formal lessons and some very good instructional books, she taught herself. Decades later, Linda is a treasure trove of lace making history, patterns, and techniques. A retired nurse, Linda is currently the resident lace maker at the Hooper-Hathaway House in Salem, Massachusetts and a member of the New England Lace Group.

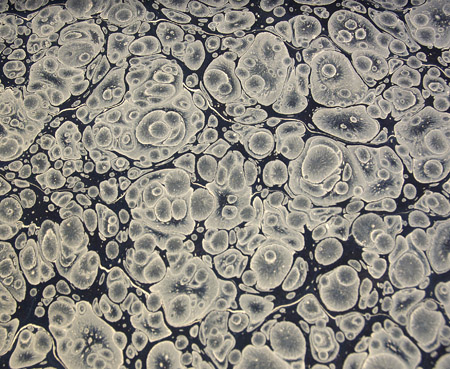

Linda weaves using 20 to 40 English bobbins, plaiting and working the lace-making fibers, which can go from 36 twos to 200 twos. (Two is the ply – the higher the first figure, the finer the thread.) To make bobbin lace, one must have tremendous patience and keen eyesight. Just look at this example of lace in the making — its pattern comes from the edging found around a handkerchief once belonging to Christian the 4th, King of Denmark, circa 1644.

Notice the size of the metal pins in comparison to the lace to get a sense of scale. The pattern is called a pricking. “This is my sheet music . . . it tells me where to go, but not how to get there. The “how” to get there is up here,” Linda says, pointing to her head. “In lace, there is a whole world of technique in just getting around a corner.”

Although lace, being woven, is technically a textile, it is more truly an embellishment. Indeed, lacere, the Latin root of the word lace, is to entice or delight. Bobbin lace, the type that Linda Lane excels at, dates back to the 1450s. “Throughout history,” Linda explains, “lace follows the dictates of fashion very closely. It goes up and down. Only the well-to-do could afford it – royalty, the aristocracy, and the church.”

And what of lace, today, I ask. Linda responds,“It’s only purpose to exist is to be pure decadence, as it [was] in years past. It’s a socio-economic statement.”

Linda Lane will be demonstrating bobbin lace making at this summer’s Lowell Folk Festival, July 25-26, 2015.