As mentioned in two recent posts, this year’s Folk Craft area of the Lowell Folk Festival will feature textile traditions. You will have the opportunity to watch artisans demonstrate techniques such as lap and loom weaving, quilting, lace making, basket making, and rug hooking. In addition, there will be a tent dedicated to the textiles and techniques used in creating what is known as the “unstitched garment,” e.g., South Asian saris, African headwraps and fashion, and Islamic hijab and abaya.

South Asian saris

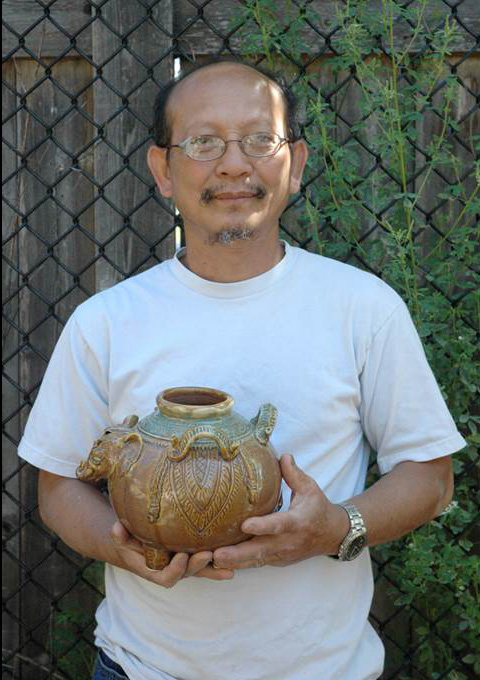

Lakshmi Narayan, Auburndale, MA

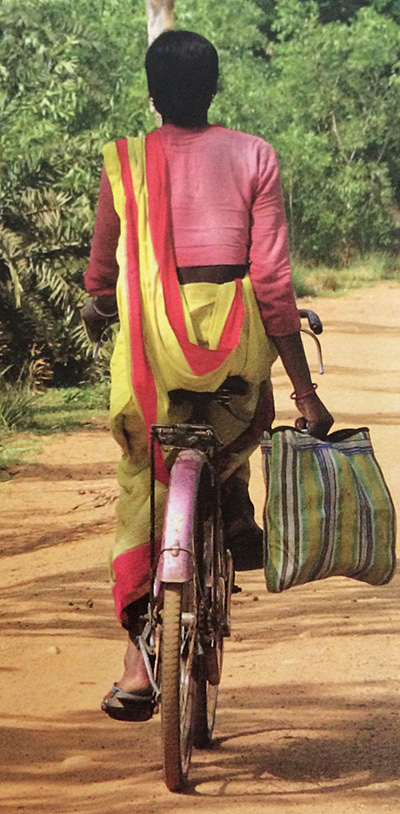

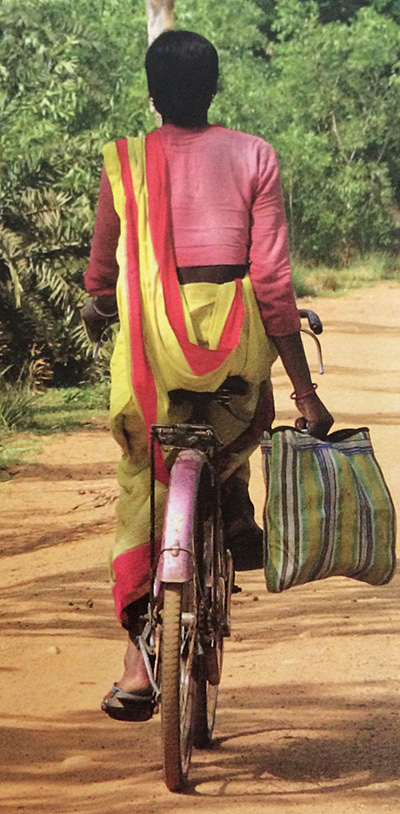

For over 1,000 years, women throughout the Indian subcontinent have worn the sari. Conceived on the loom as a 3-dimensional garment, the sari is made from a single piece of unstitched fabric 5 to 12 yards in length, that is wrapped and pleated, pulled and tucked around the body.

Lakshmi Narayan knows the sari both as cultural insider and researcher. Born in South India, she immigrated to Massachusetts with her family in 2000. When possible, she travels to India to work with people involved with Indian handicrafts and handlooms.

Lakshmi notes that there are over 100 different traditional styles of wearing the sari in India. “You could tell from the way the lady drapes her sari, which community she belongs to.” Once common for everyday wear, the sari now survives as special occasion wear, especially here in the United States. “Women now go to the tailor to have pleats stitched and pinned up. We are losing the ability to wrap the sari, something that was traditionally passed on.”

How comfortable do you feel in a sari? Lakshmi is often asked this. “I can bike miles in one, my aunt played tennis in a white sari with the British memsabs, and today it is worn with pride in corporate India to board meetings.”

African textiles, headwraps, & fashion

Roseline Accam Adwadjie, Worcester, MA

In many cultures around the world, clothing and head adornment are made by wrapping textiles around the body. Roseline Accam Adwadjie, who grew up in Liberia, says, “Africans, we wrap, but not all of our clothes are wraps. African women love dressing, they love colors. They are very elaborate in dressing.”

Roseline runs Chic D’Afrique, a store in Worcester specializing in imported African textiles. “Fabrics come in different grades,” she explains. “The highest quality of waxed cotton has a supple sheen – almost like fine leather.” She also carries plain brocades and Dutch wax prints known as Hollandaise. The latter are stiff from sizing, a combination of wax and starch. “In Africa,” Roseline explains, “after dying the cloth, they put sizing on it and beat it with sticks. They sing as they beat the sizing into the cloth – both as a way of keeping rhythm and avoiding boredom.”

African headwraps can be truly sculptural in form. Their voluminous style enhances the face, like a crown worn by a queen. Roselines more fanciful headwraps are wrapped, pinned, and sewn, thereby holding their shape. A single headwrap provides multiple looks, depending on how it is positioned. The variety is a form of improvisation, a concept fundamental to African and African American performance.

Islamic headwear & fashion:

Qamaria Amatul-Wadud, Springfield, MA

Qamaria Amatul-Wadud designs and sews clothing for Islamic women who choose to dress modestly. She is skilled in making both the hijab (headwear) and the abaya (outfit). Her creations are primarily for herself, but also for friends and family. In her Muslim community there are many women who sew for themselves, because modest, fashionable clothing is often hard to find commercially.

The Islamic hijab can be square or rectangular, and fastened with a safety pin under the chin and worn with a decorative hijab pin or headband on top. Qamaria adds her own twist to a traditional craft. She considers her style comfortable, yet elegant and modest, pointing out that her designs adhere to religious customs.

Qamaria grew up the youngest girl in a family of 10 children. She started sewing her own clothes when she was 14, following in the footsteps of her mother and older sisters. She makes outfits for every-day, party, and wedding wear, including headscarves, tops, and pants. She never makes an outfit the same way twice, preferring to “switch it up a little.” Now she is passing on the tradition of handmade clothing by teaching her young niece to sew.