Back in March, I had attended “Crowning Glories: Hat Show and Contest” in Roxbury. I was hoping to see some fancy hats, the kind traditionally worn to church by African American women. The event was hosted by the Friends of Dudley Street Branch Library and it was the first hat show they had organized. It appeared to be modeled on traditional African American hat shows and contests. Nearly all of the 30 or so women who attended came wearing a hat. Some were crocheted, others were adorned with brooches or feathers, but all in all, they were rather modest. As for seeing more elaborate hats, several folks suggested observing what women wear on Easter Sunday. “Try New Hope Baptist Church in Boston’s South End.” Folklorist friend Kate Kruckemeyer, who grew up in the South End, also suggested United Methodist on Columbus Avenue. “It’s the home church for many. There are so many cars that the police let people double-park in the middle of Columbus Avenue.”

The website of Union United Methodist indicated that Easter Sunday services would let out at 12:30. So I made my way there, arriving at 12:30 p.m. on Easter Sunday. Everyone appeared to still be inside.

There was a temporary wooden crucifix draped with a long narrow white cloth, whipping around on this windy day. The faint sound of organ music indicated that the service had not ended. A young girl entered the building so I decided to follow her inside. People were shaking each other’s hands, giving hugs, carrying Easter lilies, and generally making their way out of the sanctuary. I looked around to see a mostly black congregation, but there were some white folks too. Amidst the crowd, I spotted only one woman wearing a fancy hat. I slowly wound through the crowd and left to stand on the sidewalk outside.

About ten minutes later, the doors opened and parishioners began to trickle out. First to leave was a woman and a young boy, talking about how much they had enjoyed the service.

A few others emerged, and then the woman with the large white hat exited. I admired her outfit and asked her if I could take her picture. She smiled and agreed. Though she’d bought her hat in Baltimore, she did recall there being several hat shops in Roxbury, near Dudley station.

The lack of headwear at Union United Methodist was a bit of a disappointment. I thought I’d try to find New Hope Baptist Chruch, even though I didn’t know their Easter Sunday schedule. Got a little lost driving around the South End. Finally, as I circled around back toward Tremont, I saw a woman on her way to a large granite stone chuch, which turned out to be New Hope Baptist.

Several women were exiting the church and they were wearing large, fanciful hats. So I risked double-parking on a side street and made my way to the door. A man was about to enter and he motioned for me to go first. In the foyer were an older seated couple and an older woman on her way out. Both women were wearing hats, so I began a conversation with them, letting them know I was looking to find anyone who might make hats locally. The gentleman knew of someone names Sykes. He offered to bring me inside to try to find her. More women came out of the sanctuary wearing hats and I asked them where they got them. One answered, “Oh honey, I got this online.” As she was leaving she offered the name of several websites that sold hats. The older gentleman spoke up, with a touch of impatience in his voice saying, “No, she’s looking for a local maker.”

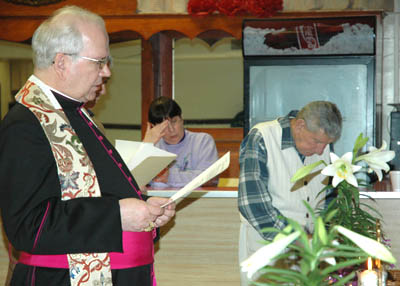

I was delighted to see he had taken interest in my quest. We walked into the hallway that separates the sanctuary from the function hall. The service, led by Rev. Willie Dubose, Jr., was still ongoing – I think I came in during the offertory prayer/doxology. The band consisted of a guitar, bass, keyboard and drums and they were rocking.

The service ended and people slowly began to make their way out. White was the predominant dress and hat color. No one seemed to mind my presence. Many seemed eager to pose for photographs.

I left after most others had gone outside. It was chilly for April and people didn’t linger. Several older women were boarding a van. Others walked. I took a few more photos.

Just as I was starting to leave, I noticed a lovely outfit on a woman who was about to get into her car. After commenting on her outfit, I asked to take her photograph.

I was fully expecting her to tell me she had bought her hat online, but asked anyway, “Do you happen to know who made your hat?” “Yes,” she answered. “I did.” Turns out, she is Ms. Sykes, the woman who several people had mentioned. I told her I’d been looking to find a local hat maker and asked for her email.

A few days later I sent her an email telling her about my interest in African American hats, my wish to learn more, and the “Head to Toe” theme of this summer’s folk craft area of the Lowell Folk Festival. I attached the photo I’d taken of her, which showed off her lovely pink hat and matching blouse.

Dear Ethel: It was a pleasure meeting you (ever so briefly) on Easter Sunday. I had admired your hat and asked you about it. Attached is the photo I took. I’d come by New Hope Baptist Church at the suggestion of several women who had organized the hat show at the Dudley Street Branch Library on March 17th. I’ve been wanting to learn more about the African American tradition of wearing fancy hats to church — and was delighted to see so many beautiful hats this past Easter Sunday at New Hope Baptist Church. Many of the women I spoke to told me they had bought their hats online or in a shop. So I am thrilled to meet you and hear you say you had made your hat yourself!

I curate the Folk Craft area of the Lowell Folk Festival ( www.LowellFolkFestival.org). This year our theme is “Head to Toe” and I am in the process of identifying traditional artists who craft a variety of head gear (hats, Caribbean carnival headdresses, crowns, head wraps, etc.) and foot wear (handmade shoes of all kinds).

I’d like to be able to learn more about your hatmaking and perhaps see if you might consider participating as a craft demonstrator at the festival. If you think you might be interested, let me know how and when I can reach you be telephone.

Regards,

Maggie

Ethel wrote back right away.

Dear Maggie:

You are very good at what you do. I will be looking forward to talking with you.

Thanks again,

Ethel

In all my years of doing folklore field research, I’ve never had anyone tell me that.

I phoned Ethel at work on 4/12/12. She’d be happy to meet with me in her home studio, as long as I can come by on a weekend. Ethel makes hats for herself, as well as for others, and still has a few hats on hand which she made for a hat show for the Shriners. She mentioned that she would be traveling to Tennessee for a school reunion, after that would be fine.

To be continued . . .