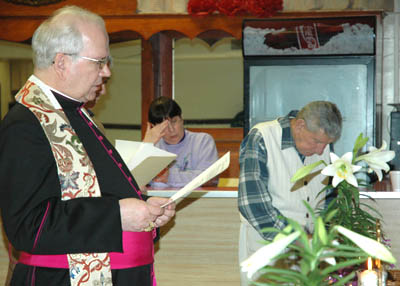

Early on the morning of July 25, just days before this year’s Lowell Folk Festival, members and friends of the Lowell Polish Cultural Committee were at the Dom Polski hall on Lakeview Avenue busy preparing rosettes, deep fried cookies in the shape of flowers. At five cooking stations, volunteers stood over electric fry pans, dipping hot irons covered in sweet batter into hot, 420 degree, oil. The Polish group plans to make 700 cookies before the weekend.

This is the fourth year Marcia (Kosik) McGrail has helped. She’s the official batter maker, joking that when she first started frying, “maybe I wasn’t doing it right, and I don’t mind doing batter, next thing I know, I was put on batter.” The rosettes are made from eggs, milk, flour, sugar, and salt, with a touch of rum. Marcia said that when her grandmother made them, she used brandy instead of rum.

Frank Makarewicz, a relative newcomer, got advice from the “master rosette maker,” Eva Kalish. His crumpled soggy rosettes were soon replaced by perfectly formed crispy brown cookies. “I need a rhythm,” he commented. He will be in charge of making kielbasa sandwiches at this weekend’s festival.

Rosettes only take a few seconds of frying on each side before they’re done. When the iron covered in batter is first dipped into the hot oil, the cookies explode into flowers.

The volunteers used two shapes of irons for a variety of rosettes.

Jane (Markiewicz) Duffley has cooked for a festival every year but one since 1974, first for the Regatta Festival, then the Lowell Folk Festival. She even worked two weeks before her wedding. Both her sisters are helping with the festival this year. I’m “older than Moses” doing this, she said, as she scurried around, picking up the fresh, crispy cookies from each station and carefully lining them row by row into large boxes.

The Polish group expected to sell out of rosettes as usual this year. The money raised from the festival will help fund Dom Polski scholarships and other worthy causes.

photos and blog by Lesley Ham